24 September 2019

We award Pompeii a full WOW!

Even though Robert had visited before, this time we learned so much about the daily lives of people at the height of the Roman Empire.

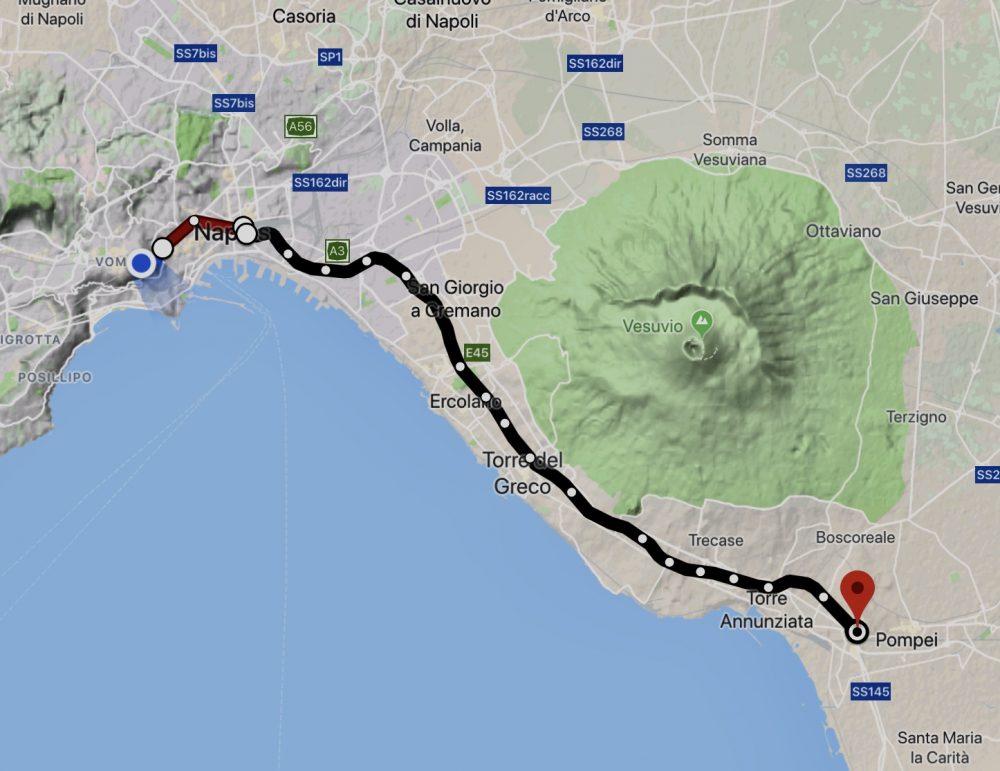

Bonnie decided that rather than drive, we should take the train from Naples to Pompeii for the day. Three modes of travel were needed: funicular down the hill from our apartment, metro underground, and train. Total time about 1.5 hours. Painless, but standing room only on the train. Bonnie thwarted one pickpocket on the train as he moved into position near an American couple on their way to Sorrento.

When you arrive at the Pompeii rail station, you are first barraged by guides, ticket sales, buses, and people hawking drinks and food.

Bonnie had arranged a tour at 2:30 through Airbnb, but we got there early to see a bit and grab a bite to eat. Once inside the gates, the atmosphere calms down. Same number of tourists but in a much larger area. We met our guide Sergio, an archeologist, along with 15 other folks. He was very good and what follows are highlights from his tour and Wikipedia.

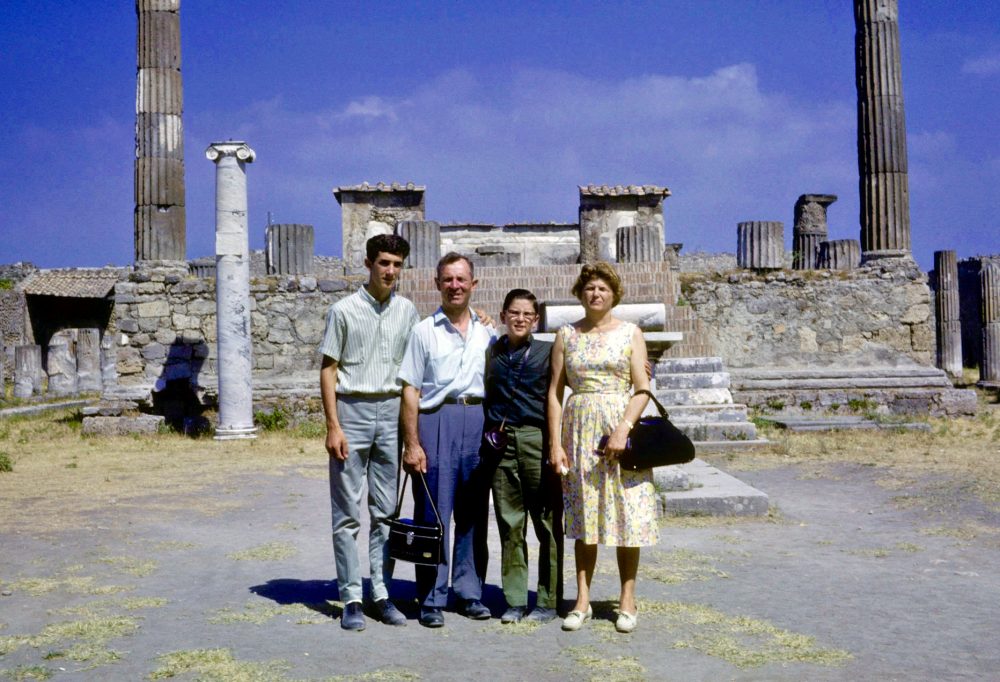

We did not know quite what to expect. Robert was there in 1962 and remembers the plaster casts of the people caught in the ash. Bonnie, visiting for the first time, was surprised by how many of the walls are standing, giving you a clear idea of buildings, streets, and neighborhoods. For her, this brought together in an exciting ways her high school Latin class and lots of recent reading about Ancient Rome. Although we have all heard about the catastrophic eruption (catastrophic for its residents but a boon for tourism today), touring the site gives you a strong sense of everyday life for Roman households.

Pompeii was a settlement long before the Romans took over. Greeks were there for a while and then locals called Samnites controlled the settlement until the Eutruscans took control. Pompeii eventually fell into the hands of the Romans around 89 BC. Of course, once it became a colony of Rome, Pompeii enjoyed a constant supply of water, good roads, a better sanitary system, etc. All of this sounds familiar doesn’t it?

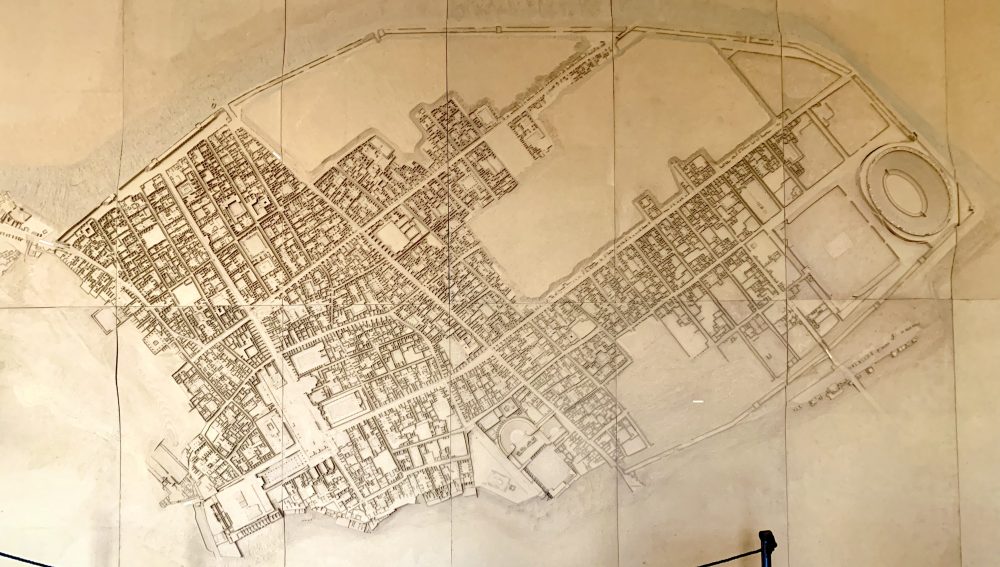

Pompei is sited on the coast on an old lava flow about 40 meters above the water. It had an important port that the volcano filled with debris. As a port town, it had extensive trading connections throughout the Mediterranean and served as a safe harbor for boats from foreign lands. It was a walled city with many gates, the most important gate met the road leading to the port. The surrounding fertile land provided sufficient produce and meat, and excellent wine that they exported far distances.

About 40 percent of the residents were middle or upper class. They had large homes with walls separating them from the street. The homes opened to a central courtyard. Around it were a place for a door guard, an office for conducting business, and perhaps several small bedrooms for the residents and guests after the home was secured for the night. During the morning, the front door was open to allow clients to enter. The guard managed the visitors and made sure no unwanted person entered the home. The roof slanted inwards to collect rainwater in a shallow pool in the courtyard called an impluvium, that in turn flowed into a cistern. There were no windows through the outer walls, so the courtyard allowed light and air into the house. Some houses had a second story.

The upper- and middle-class homes had kitchens, but the rest of residents did not. This accounts for the more than 80 food stalls uncovered to date. Plazas close to the main civic square were dedicated to sales of food, clothes, and other items. Interspersed between the homes were numerous small shops that had sliding wood doors with canopies that covered the sidewalks to shelter users from rain and sun.

Being in the place and hearing stories from our guide, we could imagine a lively trading center with business conducted in homes in the morning hours. The more well-off families gathered for meals in their homes (shut off from the street) surrounded by frescos of family members and tantalizing themes.

There was lots of street activity throughout the day. Shopkeepers hawked their stuff as they do in mercatos today. People moved back and forth on daily errands past plastered walls, many brightly painted with frescos or political campaign slogans asking for your vote. (They held elections every year.) Materials were delivered throughout the city. All of this was accompanied by smells from the open sewage system, oxen and horses, and food prepared in homes and food courts.

Most sidewalks were ample to handle the number of pedestrians running errands or going to the public baths. If you were confused about where you were in the city, you could look at one of the water fountains. Each had a unique carved figure specific to its neighborhood.

There was an outdoor amphitheater for plays and a smaller covered theater for music recitals, both free to the public, although the seating for dignitaries, middle-class males, and women was segregated. And, of course, the legal and illegal brothels provided further entertainment to a segment of residents and visitors.

Of course, all of this came to an end.

While the residents of Pompeii were used to frequent small earthquakes, they experienced a devastating 5.0 to 6.0 earthquake 17 years before Mount Vesuvius blew. The Romans were in the process of rebuilding the city and had not finished all the work at the time of the eruption.

Before the earthquake, there were about 18,000 residents. Afterward, the number was only 12,000 because some had moved away. Mount Vesuvius had not erupted in 1,200 years so no one was prepared. Vesuvius erupted in November 79 AD. Many people were killed by inhaling the toxic gases before they were covered in 13 to 20 feet of ash.

Pompeii’s location was unknown for centuries. It was thought to be only a myth. Then in 1592 a construction project revealed some traces of the city. This prompted excavations (looting) to retrieve statues, marble, and other artifacts. This grab-and-go action also took place shortly after the eruption. Archaeologists recently found graffiti on a house shortly after the time of the eruption that said “house dug.” Professional archaeologists took over excavation in the 1860s, resulting in what we see today. One third of the total 170 acres remain to be uncovered because current funding has been focused on preserving what has been unearthed.

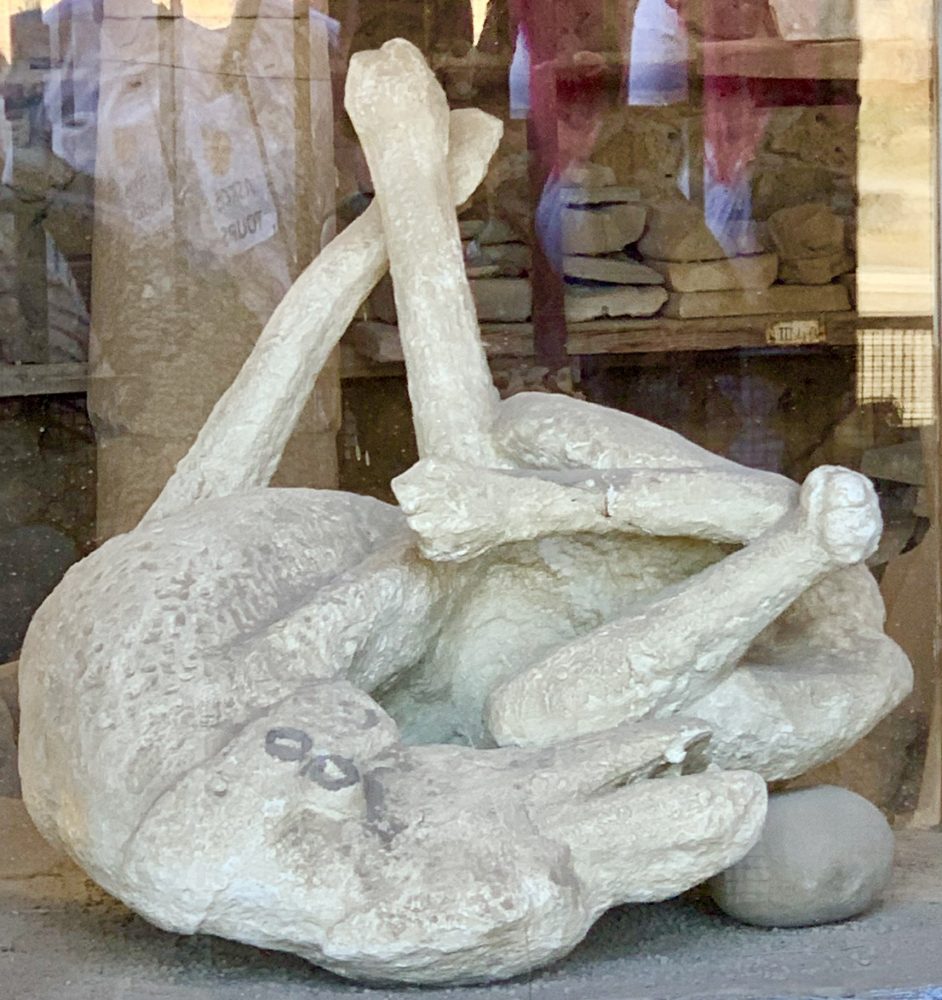

In the 1800’s, archeologists made plaster molds of the voids left in the ash after the bodies decayed. Several are on display, including a dog. Robert remembers these from 1962 and a National Geographic issue on Pompeii. They no longer make plaster molds because it degrades what remains for analysis.

As we stood in the midst of what is left of the city, having walked its streets and plazas and hearing stories from our guide, we could imagine that real people lived here. So glad we came.

We highlight more of what we learned in the photographs below.

And for those of you anxiously waiting for the X-rated portion of this post . . . be patient. It is at the end.

X-Rated Pompeii

All these people are waiting to see paintings on the walls of one of the legal brothels in Pompeii. Phalluses carved into the street stones directed clients to the brothels. Today, you can have your guide lead you there or use a map.

Scholars believe the erotic paintings served two purposes:

1. Provided a menu of what was offered in the brothel,

2. Gave how-to instructions for first-time clients.

We have added photos of other erotic paintings and artifacts taken from Pompeii years ago and placed in the National Museum of Archaeology in Naples. Kirk P. remembers he and Adria taking their teenage kids there.

We should note that phallus symbols could mean, beyond the obvious, power and happiness. The people of Pompeii were not shy about displaying such images at their thresholds or on the walls of their homes.

And Robert remembers none of this from his trip to Pompeii with his parents in 1962!

Glad you took the train! But sorry you had to stand up!!